Rapid Task Analysis for Performance Support

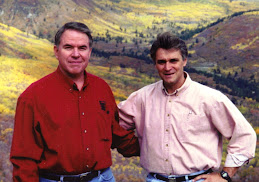

Recently Bob and I hosted a webinar for this growing Performance Support Community. During the session, we discussed Rapid Task Analysis. Here is a summary of what we presented during the meeting. The slides and a job-aid checklist are posted in the members portion of our performance support wiki. Once you have read this article, enter any questions you have in the comments section at the bottom of this article. Bob and I, along with other members of this community will then respond. Hopefully, we can all emerge with greater understanding in how we can implement this vital process in our Performance Support practice.

What is Rapid Task Analysis and why is it important?

Fundamental to any Performance Support strategy is the identification of the performance tasks the strategy needs to support. In addition, since tasks don't stand alone but actually orchestrate into higher work-flow processes, a solid strategy also requires the determination of those processes. Rapid Task Analysis is an approach for accomplishing this. Rapid Task Analysis has two functional objectives:

- identify the job-specific tasks and related concepts according to a predefined scope objective

- organize the tasks and concepts into meaningful business processes

RTA is rapid because it involves subject-matter experts who understand the work environment as well as the tools (such as software applications) that need to be used to complete specific job tasks Using SMEs eliminates the time-intensive requirement of the developer becoming an SME. It is also rapid because it is a relatively simple, straightforward process that SMEs readily understand and as a result become more efficient over time in providing the information needed.

There are three primary phases of a Rapid Task Analysis: prepare for a RTA session, conduct a RTA session, and finalize the RTA.

Phase one: Prepare for a RTA Session

In this preparation phase you do three things:

- Define a scope objective

- Analyze existing performance support resources

- Set up a RTA session

A scope objective establishes the parameters for the task analysis. Its purpose is to help SMEs focus on the correct and complete set of tasks and related concepts. Analyzing existing content and curriculum within the confines of the scope objective will help you more efficiently guide SMEs through a task analysis session. Setting up a RTA session includes scheduling the session, identifying and inviting your SMEs, establishing an agenda, and assembling the necessary materials.

1. Define a scope objective

As mentioned, a scope objective establishes the parameters for the task analysis. If you fail to establish a precise scope objective, you may end up identifying irrelevant content. This could add unnecessary work and threaten your ability to adequately meet your audience's requirements.

You should create a first draft of the scope objective prior to attending the task analysis session. The objective should then be validated by your SMEs at the very beginning of the task analysis session.

What are the primary components of a scope objective?

There are two primary components of a scope objective. The objective should define the audiences and the global performance outcomes.. The following example shows a scope objective with these components.

SAMPLE SCOPE OBJECTIVE: The mission of this task analysis is to identify all the tasks and related concepts that network engineers at levels four and five need to perform and understand in order to plan and integrate in their networks all of the new features in Release 5,0.

Types of audiences

Identification of the type of audiences is a critical delimiter for your scope objective. You want to target multiple audiences in your scope objective only if there are potentially different content requirements for those audiences. If they clearly have the same requirements, then find a single label that encompasses all of tne sub-audiences. Sometimes you may have what appears to be a single audience, but within that audience there are differing levels of expertise. These levels may call for unique content. If this is the case, then it is appropriate to declare the levels in your

scope objective,

Global performance outcomes

These outcomes need to provide a performance umbrella for all the content you will be identifying during the task analysis. You should work with your SMEs to ensure that these global performance outcomes aren't too broad or too narrow.

Once you have a scope objective what do you do with it?

Your scope objective needs to guide the task analysis session. You should post it where everyone participating in the analysis can readily see it. Throughout the session, periodically review the scope objective and check to make sure the tasks and concepts you are identifying fit Within that scope.

On occasion, you-may find, as you proceed into a task analysis, that you need to modify the scope objective. It's OK to do this. It may deserve being narrowed or broadened as a result of insights that naturally occur throughout the process.

2. Identify and analyze existing performance support solutions

Skipping this step can potentially create more work for you and your SMEs. If you complete this phase prior to the task analysis session, you can potentially shorten it by identifying tasks and concepts that have already been identified in existing performance support tools. This can then serve as a springboard for beginning the analysis session.

If, on the other hand, you complete this step after the session, you may find concepts and tasks that have been missed. It then takes additional time and effort to verify the content and assign it to the appropriate groupings. Sometimes groupings, with the new additions, require re-chunking. Hence, more work and more time.

What should you look for?

Once you have drafted your scope objective you can begin looking for performance support solutions that currently exist to support and train the same kind of audiences in other areas of your organization or in competing or similar organizations.

As you review existing tools, look primarily for tasks and related concepts. Don't try to organize them. You'll do this during the task analysis. Just start a list of tasks and a list of concepts. The exception to this is if you find a source where someone has gone before you and actually organized tasks and concepts into logical groupings that would potentially work for the audiences you nave identified.

How much time and effort should you put into this?

It all depends on how much time you have. And, if you have a normal job, it's not much. Begin by setting aside a small but focused, amount of time to determine if it is worth spending more time in this kind of research After a couple of hours, if your efforts yield no fruit, then bag it - move on to more productive work But, if you find promising leads, or better yet, strike a rich cache of information, invest more time.

What if there isn't anything to analyze?

Then skip this phase and don't worry-about it. Since you are inviting SMEs to the task analysis, you'll get the information you need there.

3. Set up the task analysis session

Setting up a RTA session includes scheduling the session, identifying and inviting your SMEs, establishing an agenda, and assembling the necessary materials. The following Is an example of a potential agenda:

SAMPLE SESSION AGENDA

- Introduction

- Discuss scope objective

- Define terms

- Identify tasks

- Group and label tasks

- Organize tasks groupings

- Identify concepts

- Establish a path forward

Who and how many should attend the task analysis session?

If the mission of your scope objective includes supporting performance that requires the use of technology, you need, at a minimum, participants whose collective understanding represents the full functionality of the technology and also the use of that technology from a customer or a business perspective. Often, those who have an in-depth technology view lack a legitimate business perspective. Clearly, in such cases, you need to invite additional people to ensure you have adequate coverage of both technology and business areas.

It is helpful to have at least two subject matter experts. If you only have one, it generally takes longer and you have a higher probability of a skewed view, (Although it is possible to nave one person who "knows it all." In such cases one person is all you would need.) Typically, when you have two or more, they tend to check each others' views and push for a more balanced and comprehensive consensus.

You may also need more than two SMEs to ensure you have a sufficient balance of additional expertise. Depending upon the mission of the task analysis, you may also find other kinds of subject matter experts helpful, for example legal, safety, governmental regulation, or cross-cultural specialists.

The bottom line is you need to identify people who understand what it is that the organization needs their people to do and know to be competent in their work within the parameters of your scope objective.

It is possible to have too many participants at a task analysis. The more you have the higher the probability of getting bogged down in debates between opposing factions. You need to keep the size of the group manageable. Generally, more than ten SMEs becomes unmanageable - two to five is a better number. Once you have a draft of the results of your task analysis, you can circulate it to a larger group of SMEs for feedback and buyoff.

How do I talk busy people into attending a task analysis?

The question you need to answer for these people is "How will my life be better if I attend?" There can be several answers:

- A task analysis can help minimize and focus the time you need from your SMEs

- The process of task analysis can provide a functionality check on technology development efforts. Your technology SMEs will find that as they go through this process, they will be able to use the results to check and often improve the functionality of the technology. If there are any areas where the technology and the business requirements are not compatible, they will surface during the task analysis.

- Task analysis helps strengthen the business value of technology. A task analysis makes it clearer how the technology contributes to the way people work in the organization and what they need to do to address business needs.

- Finally, task analysis often brings greater order to the chaos of how people work in the organization. It brings technology and business processes together that result in organizations actually using technology to meet real business requirements. Sometimes it takes the experience of task analysis for SMEs to fully grasp the benefits listed above.

How long should a task analysis last?

The required time depends upon the scope of the task analysis and the experience of the group. This isn't a time-consuming experience. The first time you work with a group of SMEs will take longer than subsequent sessions. You will find that once they have become conversant with the

process, they will attend the next task analysis with most of the work done before they arrive. The difference will be dramatic.

It's often wise to allocate more time than you estimate it will take with a group of SMEs. It's always easier and more positive to let them go early (because they did such a great job) than hold on to them beyond the amount of time scheduled.

Once you nave conducted several task analysis sessions, you will have a good feel for estimating future sessions. For your first task analysis you may want to leave the duration open-ended. For example, "Our first task analysis session will run from 8 AM until noon. Once we complete that session, we will schedule an additional session if needed.

What tools do I need to hold a successful task analysis?

Task analysis is a "brainstorming" activity that is dynamic in nature,

especially at the beginning. You need tools that will accommodate making

rapid changes to task listings in a way that all participants can see what

you are doing. This can be accomplished with:

- A white board

- At least one flip chart (two would be better)

- A set of multi-colored markers,

- A means for posting flip-chart sheets (e.g., masking tape, tacks, etc.)

- Extra writing pads and pens in case your SMEs fail to bring them. (They will want to make notes on their own during the task analysis process-)

Consider posting the mission objective for the specific task analysis on a flipchart sheet for all participants to reference throughout the session. The whiteboard should be your primary tool for initial identification of tasks. Once you have identified them and grouped them, transfer the

groupings to tne flipcharts and post them.

Phase two: Conduct a RTA Session

During this phase, you conduct a RTA session. During the session you work with SMEs to:

- Prepare them to participate in the session

- Identify as many potential business tasks as possible relating to the scope objective,

- Organize the tasks into logical groupings that reflect business processes.

- Establish a business order within and across the groupings.

- Identify the associated concepts for each of the groups of tasks.

1. Prepare your SMEs to participate in the session

As you begin your RTA session there are three things you need to do to prepare your SMEs to participate:

- Set them at ease.

- Finalize the scope objective.

- Prepare the SMEs to help identify tasks.

Regardless of the type of meeting, there is always value in taking steps, up front, to relieve any concerns participants may have. Common concerns include how long will this meeting last, what is my role in the meeting, what specifically will we be doing, and who are these other people? These concerns can be alleviated as you welcome them to the session, introduce everyone, and briefly discuss the agenda.

One of the first agenda items should be finalizing the scope objective. As you introduce the scope objective, solicit feedback from your SMEs to ensure that the objective is complete, clear, and meaningful from the perspective of the audience(s) and organization(s) the performance support solutions are meant to serve.

The most critical step, though, at the beginning of a RTA session is preparing SMEs to help identify tasks.

What do I need to do to prepare the SMEs to help identify the tasks?

The first and most critical step is you need to teach them the difference between a task, a step, and a process. You do this at the beginning of the task analysis. They need to see examples that they can relate to. And you need to ask them enough questions to feel comfortable that they understand the difference. If you fail to teach this, your task analysis will rapidly evolve into a state of total chaos.

You may want to write the definition of a task with a couple of examples on a flip chart and post it where your SMEs can review it during the session. In the early stages of identifying tasks, you may want to refer to the definition to make sure the tasks are tasks. The first hour is the toughest. But, as your SMEs move into this process, at some point, the light will go on and they will understand what a task is. At that point, they will transition to "warp" speed.

What is a task?

A task is a discrete set of steps that together achieve a specific outcome. For example, the following set of steps makes up the task of "Entering a Phone Number n Your Cell Phone for Quick Dialing"

SAMPLE TASK:

- Step 1: Press the END button to clear all options.

- Step 2: Press the right button under the menu option: Names

- Step 3: Press the down arrow one time to highlight the menu option: Add new

- Step 4: Press the left button under the ;menu option: Select

- Step 5: Use the keypad to enter the j name of the person whose number you will be adding.

- Step 6: Press the left button under the menu option: OK

- Step 7: Use the keypad to enter the phone number.

- Step 8: Press the left button under the -menu option: OK

These eight steps, together, comprise only one task In a set of related tasks. For example, in addition to "Entering a Phone Number for Quick Dialing" there is the related task of "Quick Dialing a Call." This task would automatically dial one of the numbers entered for quick dialing.

Another task would be "Automatically Entering the Phone Number of the Person Who Just Called you." Each of these tasks has a discrete set of steps that accomplish a specific outcome, and each task belongs to a larger group of related tasks.

What is a step?

A step is a discrete action that does not stand alone in its ability to achieve a practical outcome. For example, turning on an iron is a step, and there is an outcome of the iron becoming hot, but the practical outcome of ironing something is not achieved by completing this singular step. There is the step of adjusting the temperature dial. There is a step for setting the amount of steam, and there are other steps that must be completed to achieve the practical outcome of ironing something. Sometimes, in task analysis, SMEs mis-identify steps as tasks. You should continually check each task by asking the SMEs to estimate the number of steps it takes to complete it. If they say "one step," it isn't a task.

Note: Entering a single command isn't a task unless there are multiple steps in executing that command. Most often, it takes multiple commands to achieve practical outcomes.

What is a process?

A process is a set of tasks that can be orchestrated together to achieve a broader outcome. There are often decision points in the process that branch to different tasks. In the case of a process, each task Is a sort of macro-step, Put behind each macro-step is another set of discrete steps.

As you conduct a task analysis, watch out for processes. Many processes are obvious. You can check for them by asking your SMEs to describe some of the steps. As they describe a "step," check to see if it's really a task (e.g., if there is more than one discrete step required for completing the proposed "step."}

When you identify a process, decompose it to its individual tasks. Be careful not to allow these processes to influence how you will eventually group your tasks into logical groupings. Once you have identified all the tasks, you may find that different process groupings are more meaningful for your learning audience.

2. Identify tasks

Once you have taught the fundamental concepts SMEs need to understand to identify tasks, you can then begin identifying them. Don't try to identify the tasks in any organized way. Simply start a list of tasks. As your SMEs propose tasks, ask questions to ensure they are tasks rather than processes or steps. This is especially important as you begin the session. A question that is often helpful In validating a task is "Approximately how many steps would you say are in that task?" If the SME responds, "One," Then you have a step, not a task. If the SME says, "Ten or twelve" then you may have a task. It is wise to follow-up by asking, "Are there sub-steps nested within those "Ten or twelve" steps. If they say yes, find out how many. There is a chance

that each of those "ten or twelve" steps is a task rather than a step. It is also important that you continually check the tasks to ensure they represent tasks people perform on the job rather than tasks people follow to use a specific feature of a software system.

A helpful standard to set while you are identifying tasks is to describe each task in performance rather than non-performance terms (for example "Register a Patient" rather than "Patient Registration"). You can facilitate this by asking SMEs to complete the sentence "Learners need to know how to..."

As you move through this procedure for identifying tasks, continually seek for consensus between the SMEs. They should agree that each task fits within the domain objective and has legitimate organizational value. Where there isn't consensus, make a note and resolve it in phase three of the RTA process.

Why not identify processes first and then identify the tasks for each of

those processes?

If you begin by identifying processes and then decompose them to identify the tasks, you'll potentially end up with "out of balance" task groupings (e.g., some groupings with 12 tasks and others with only two or three). And there is the possibility of failing to identify more meaningful groupings because you have opted to embrace traditional, existing, processes. If you strip tasks from existing processes and then rethink groupings based upon the current performance requirements of your audiences, you may end up with new and more efficient processes. And, if not, you have at least challenged the current processes and found them acceptable.

What do I do if my SMEs disagree?

Some of the best insights emerge from conversations where there is disagreement. Your job is to facilitate the discussions that SMEs have as they seek to meet the requirements set out by the "scope objective." What you need to watch out for are discussions where participants get off

track. Often times the disagreements have little to do with whether a task or concept should be included. If, by some chance, you find SMEs disagreeing whether a specific task or concept is appropriate, and it appears that the issue can't be resolved, end the discussion by acknowledging that there is an issue that needs to be resolved and that you will include it for now but will verify it with a broader audience of SMEs after the task analysis session.

3. Group the tasks by chunking and labeling them

Once your SMEs conclude that you have identified all of the tasks, ask them to help you group them into logical groupings according to how people would generally perform them on-the-job. As you move through this procedure, be sure to apply the principle of chunking Chunking, in this case, is limiting each task grouping to a range of five to nine tasks. Research has demonstrated that more-than nine items overloads a learner's ability to store Information in long-term memory. Fewer than five items results in more chunks (groups) which can also threaten retention and increases the burden of instruction. Each of these chunks will become a learning module. If you have chunked properly, they will also represent a business process. You will

best serve your learning audience if you keep each of the modules balanced by following the principle of chunking. Labeling is also important. The label you put on each task grouping defines why those tasks have been chunked together. The right label will help learners understand the rationale for the grouping and as a result enhance their ability to associate the individual tasks together. This will add instructional integrity to your e-Learning system.

Make sure you follow the same guideline for labeling your task groupings as you follow for your individual task labels - use performance labels (for example "Posting Charges and Reimbursements" rather than "Charge and Reimbursement Posting").

How do I involve the SMEs in grouping the tasks?

Do the following:

- Teach your SMEs the principle of chunking. Include a discussion of the benefits of applying this principle. Emphasize the need for the groupings to be meaningful from the perspective of how the audiences will perform the tasks within the organization (e.g., on-the-job).

- Once they understand the principle of chunking, provide them a listing of all the tasks. You may already have them listed on the whiteboard or posted on flipchart pages. What's important is that they are able to see all of the tasks together.

- Allow your SMEs time to review the tasks and consider how they might be grouped. Hopefully you have SMEs in the session who understand your audiences and how the organization needs to employ the tasks to achieve what matters most in that organization. These SMEs need to drive this chunking and labeling process.

- Chunk the tasks as a group. You may find it helpful to set the stage with a scenario similar to the following: Pose the question: "I've just been hired and you have been assigned to train me in my new job. What is the first set of tasks that I would need to learn? " As the group Identifies the tasks, put the number "one" next to them. Then put the number "two" by the next set of tasks and so on,

- Once you have created the groupings, teach your SMEs the purposes and guidelines for labeling. Then work with the group to label each chunk.

How critical is it if there are more than nine or fewer than five items in a chunk?

You should strive to have your chunks fall within the range of five to nine. But it is more important that the groupings be logical from the perspective of your audiences. If that logic requires a chunk greater than nine or smaller than five, then allow it. If you consistently have groupings that violate this principle of chunking you present a significant instructional threat to those audiences. There is either too much information in the grouping for them to store and retrieve from long-term memory, or there isn't enough information in the chunk for them to

adequately associate as a grouping, You can also make more work for yourself in the case of smaller chunks. Every chunk contains a set of tasks and the possibility of an associated set of concepts. But when you develop learning to wrap around those tasks and concepts in a chunk there is also contextual information to write that addresses the relationships of these tasks and

concepts. Also, if you create more chunks than is instructionally necessary you create more development work when you begin to wrap training components around the chunk (such as practice exercises or demonstrations). This dramatically increases development time and costs.

How does chunking apply to tasks, steps, and processes?

During task analysis you should first chunk the tasks into logical groups. Each of these groupings becomes a process. If you have more than nine processes you should chunk them into macro processes. However, you should not identify steps during the chunking process. This would add unnecessary time to the task analysis session. But when the time comes to document tasks, you should only apply the principle of chunking loosely, if at all, to the steps. You may find it helpful to nest some simple related steps together if the nesting will be logical to the reader. Often, a task requires more than nine unnested steps and that is simply the nature of the task.

Why distinguish concepts and tasks by label type?

When learners look at a label, they need to determine by that label whether it is a concept or a task. It is frustrating to waste time accessing the wrong kind of content. From both a reference and learning perspective, people have very different needs when they access task information versus concept information. It doesn't take much to clearly convey this difference. As you consistently use verb labels (e.g., create a new document) to represent tasks and noun labels (e.g., document creation) to represent conceptual information, learners will intuitively recognize these two different types of content. This standard labeling practice is a key step to

establishing, and therefore realizing, the benefits of an overall Consistent Learner Interface (CLI).

What other labeling guidelines should I follow?

As you establish labels, consider the following guidelines

- Provide enough detail. Labels can be too brief. They need to distinguish the associated content from all other content. Sometimes that requires investing more words in a label. For example, suppose you were developing training for a specific IP routing protocol called FAST; and in the task analysis you identified the concept: Instance and Router ID. This label may not sufficiently distinguish the specific content relating to FAST from similar content for a different routing protocol. You could strengthen the label by adding more detail. In this case the label could become; Instance and Router ID for FAST,

- Use audience focused language. The language you use for labels needs to reflect the performance culture of your audiences rather than the culture surrounding the subject matter (for example, technology). Often the language surrounding the subject matter is foreign to that of the learners. Sometimes, developers become so close to the subject matter, they forget their audience lacks the same familiarity. You should guard against letting the culture surrounding the subject matter drive the language of your labels. For example, instead of the label "Completing the PF4-09 Screen" you might use the label "Entering a Patient's Billing Information." Or instead of the label "Using the Electronic Clipboard" you might consider a less technical one like "Cutting and Pasting Information." Or if your audience wouldn't understand the analogy of "cutting and pasting," the label might read: "Moving Selected Information from Place to Place." Again, the intent

of this guideline is to use language that will be most familiar to your audiences; language that reflects that business environment and culture. Avoid "cop-out" verbs. Sometimes, when attempting to convey performance, SMEs will use "cop-out" verbs. This is often the case when technology is involved. "Cop-out" verbs don't address the actual task that the learner needs to accomplish. For example, "Using the toolbar" does not describe what the user's goal is. The user wants to accomplish a business goal; no company would establish "Using the toolbar" as a business task. When your SMEs suggest a label with gerunds

such as "using," "working with" and "managing" as a part of the label, ask the question, "What does the user want to manage/work with/use this to accomplish?" Put another way, you could say, "The customer uses X to do/achieve ," and ask the SMEs to fill in the blank.

4. Establish ordered relationships

One of the reasons why you chunk information are to facilitate a learner's ability to:

- Remember what they have learned.

- Integrate related performances and concepts into overarching skill sets.

These objectives can not be accomplished by only grouping items. You must also establish an ordered relationship of all the groups (chunks.) And the items within each grouping also need a defined order. If learners grasp the logic of that order, they will use that logic to more effectively store what they learn in long-term memory and also retrieve the newly gained knowledge and skills when needed.

One of the greatest performance challenges organizations face is helping learners integrate the mastery of related tasks and concepts into overarching skill sets. This isn't easily achieved unless people understand how specific tasks and concepts relate to each other. It is even more critical for them to understand how the different groupings (processes) relate to one another. Establishing an ordered relationship plays a critical role in achieving this.

What are the guidelines for establishing an order?

The primary guideline for establishing an order is to order tasks and processes (task groupings) according to "best practice" of how primary audiences would perform on-the-job.

In addition, consider the following:

When there isn't a clear hierarchical relationship, use a typical first-day-of- work scenario as a guide. For example, "I was just hired today and-you have been as-signed to train me to do my job. What is the first process I would need to learn? In that process, which is the first task I would need to learn?"

When you are identifying content for multiple audiences, always attempt to establish a single generic order for all audiences. But, if that order provides a logic threat to a specific audience, then establish a unique order for that audience. Note; After you identify concept (see next section), you will also need to order them within each task grouping. Order concepts based upon their relationships to the ordered tasks. List concepts that are global first (i.e. concepts that relate to all the tasks in a process).

5. Identify the concept requirements for each process (task grouping)

Once you have identified, grouped, and labeled the tasks, you can now efficiently identify the concepts learners need to master in order to perform with understanding. Concepts provide the context for performance. They answer the questions of what, why, when, where, and who. Learners become competent only when they understand the conceptual underpinnings of the tasks they perform. Failure to teach concepts can have severe consequences to learners and their organizations. When learners lack a conceptual understanding behind what they have learned to do, they are less able to adapt to changes in their work requirements. They require more on-the-job support. It takes more time for them to master other related tasks. They are more likely to forget what they have been trained to do. Real competence requires the understanding of "what about" wrapped around and integrated throughout those "how to's."

What is a concept?

Where tasks describe how to do something, concepts provide the understanding behind those tasks. A concept is information that describes, at a minimum, what something is (and sometimes what it isn't), and why it is important. In addition, a concept may address who is influenced by it, when it may do that influencing, where the influencing takes place, and how often or how much. The only thing a concept doesn't address is how to do something.

For example, the concept of "Quick Dial Options" would:

- Provide understanding for cell phone tasks such as Entering a Phone Number for Quick Dialing, Quick Dialing a Call, and Automatically Entering the Phone Number of the Person Who Just Called You,

- Describe what "quick dial" is and the various "quick dial" options available. It could include an example in the form of an analogy or a scenario. This concept would also explain the benefits of these options. It could also describe situations when these options are helpful.

- It could also provide related information such as the number of phone numbers that can be stored for quick dial.

All of these together would comprise the concept of "Quick Dial Options."

Why wait until now to identify concepts?

Even though, concepts are most often introduced or taught prior to tasks, the process of task analysis is just the opposite. In a task analysis, you identify tasks first, followed by concepts. Concepts are justified by the existence of tasks. If you identify the tasks first and organize them logically, it becomes much easier to then identify the relative concepts associated with those task groupings. Doing this avoids the probability of great confusion. Often, while you are identifying tasks, SMEs will also mention a required concept. These can be written down, but you should quickly direct the focus back to identifying tasks. Focusing on tasks first will help you complete the process of task analysis more quickly and with less confusion. And, in the end, the concepts you identify will be adequately justified by the tasks they support.

What is the difference between a concept and a term?

Concepts and terms differ in scope and investment. A concept is generally much broader than a term and requires a more significant learning investment. A term is narrow and often only requires a brief definition to achieve the level of understanding required. A concept sometimes requires the definition of specific terms to ensure readers gain sufficient understanding. In some cases, the same word can be a term or a concept depending upon the understanding requirements of the audience. For example, the word "mouse" is a term if all that the audience requires for an understanding is that it is a "hand controlled device used to move the cursor and make selections on a computer screen." But if the audience is computer illiterate, a mouse could easily become a concept where an analogy is added to the definition along with animation showing an example of a mouse in action. Added discussion of different mouse buttons and styles with the advantages and disadvantages of those styles would quickly turn "mouse" into a concept.

What if I identify more than nine concepts for a given process (grouping of

tasks)?

The easiest solution is to combine multiple concepts into a larger single concept. For example, if you had the concepts of "Object Types" and Object Structures," you could possibly combine them into the concept "Objects." But, if your concepts are independently substantial In their scope and importance to your audiences, you should keep them separate.

In such cases, if you only have one or two additional concepts, you could choose to have a chunk that exceeds the guidelines. This is less serious if the majority of concepts aren't complex in nature. If they're complex, however, it is appropriate to divide the concept chunk into two chunks. If you do this, look for concepts that are more global in nature that potentially relate to other processes (groupings) as well. This additional grouping of concepts could then become a separate learning module In this phase, you finalize the results of your task analysis session by having it reviewed by a broader range of SMEs including potential learners for completeness, clarity, applicability, and acceptability.

Phase three: Finalize the Results of the RTA Session

After a successful RTA should have:

- An ordered list of all of the tasks that fit within your scope objective

- All of the tasks grouped into processes, and the processes grouped into higher level processes, if applicable.

- The concepts that require understanding in order to perform these tasks and move through the processes

- Standardized labels for tasks, processes, and concepts

After the task analysis session, create an outline with all the task groupings (processes) in the order determined by your SMEs. Here is an example of a single process (task grouping) with its associated concepts and tasks:

Contacting and Managing Your Friends in Facebook

Concepts:

- The Message Wall

- Friend Network Options

- Facebook Email Management

Tasks:

- Post a message on a friend's wall

- Track Your Emails

- Track Your Friends

- Establish a network

- Browse all networks

- Compose and send a message

- Locate a Friend

All of your task groupings should appear similar to the above example. This outline can then be sent to the SMEs who attended the RTA session for their review and approval. Once you have that approval, you should extend that review to a broader range of SMEs including potential performers. Their role is to provide a validity check. You want to know from them if there are tasks or concepts still missing from the list, if each of the labels makes sense, and if the concepts and tasks will support meaningful performance in the organization.

Once you nave adjusted the outline to address the feedback you received from SMEs, you have completed a Rapid Task Analysis.

Rapid Task Analysis is not only helpful in developing your performance support strategy, it also provides you the scope and sequence for formal learning events. This outline can guide you throughout the development of all formal and informal learning solutions. Each process grouping (like the example In the previous section) contains a listing of concepts and tasks that should comprise a Learning module. The RTA outline can also be used to guide your overall project planning and management. It can help SMEs provide focused assistance and content development. All in all, it is a fundamental practice that can bring continuity to all we do to support performers in all five of their moments of need.

Wow - thanks for this detailed blog posting Con....I was unable to attend the webseminar, so appreciate the effort it took to put this together.

ReplyDeleteNow I will go and watch the archived seminar to get the "full" experience!

Carol

Hi Conrad,

ReplyDeleteThanks for a really nice RTA Webinar and this follow-up. At your convenience, please address the following questions ...

How do you order equally weighted tasks (e.g., tasks representing different decision branches, or possible outcomes based on a particular decision point)?

Aside from ordered relationships, how does RTA handle associative relationships (e.g., among tasks across different processes)?

Besides concepts, what other supporting information would you consider (e.g., policies, factual information, tools/systems, media)?

How do you handle alternative tasks (e.g., standard vs. variant task)?

How do you ensure that tacit information is extracted from SMEs during an RTA session (particularly information SMEs consider so automatic, they are unlikely to cite it)?

What other information would be useful to obtain during an RTA -- audience information, general task attributes (criticality, complexity, error consequences, frequency, etc.), pre-/post-requisites, etc.?

What must be in place on the business side to ensure a successful RTA session?

In addition to developing content that is aligned with business processes, is it possible to extend that alignment to the overall business case and objectives (and justifications and priorities)?

Besides George A. Miller's seminal article, "The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information," what other articles re chunking would you recommend?

Again, thanks.

- Rich Pagano